Most of the World Is an Adorably Suffering, Debatably Conscious Baby

Thoughts after five months of fatherhood

There are some moments of your life when the reality of suffering really hits home. Visiting desperately poor parts of the world for the first time. Discovering what factory farming actually looks like. Realising too late that you shouldn’t have clicked on that video of someone experiencing a cluster headache.

Or, more unexpectedly, having a baby.

One of 10²⁰ Birth Stories This Year

With my relaxed and glowing pregnant wife in her 34th week, I expect things to go smoothly. There have been a few warning signs: some slightly anomalous results in the early tests, the baby in breech position, and some bleeding. But everything still seems to be going relatively well.

Then, suddenly, while walking on an idyllic seafront at the Côte d'Azur at the turn of the new year, she says, “I think my waters have broken1”. Really? It’s probably nothing, let’s just check whether that’s normal. After a quick consultation with ChatGPT and a crash course on premature membrane rupture, we realise—yes, her waters have definitely broken, and we’re among the 7–8% of parents who’ll have a premature baby. We awkwardly call the hospital. They tell us to come in immediately.

One slightly leaky bus journey later, and we’re at the maternity ward. No contractions yet, but the doctors tell us that they might start over the next few days. If they don’t come within the week, they’ll induce labour. They prepare a room, and ask how we want to do this, nudging us towards a caesarean.

With no bed for me, I head home to get some sleep. At 7am, the phone rings: she’s having the baby. With no buses running, I sprint to the hospital, take a wrong turn, and rather heroically scale a three-metre wall to avoid a detour.

Bursting through the hospital wards, smelling distinctly of sweat, I find my wife there, in all green and a mesh hat, looking like a nervous child. We’re allowed to exchange an awkward “good luck” with everyone else watching. Hospital regulations probably allow a kiss, but Anglo-Chinese cultural norms most definitely don’t, so a pat on the shoulder, and she’s taken into theatre.

For the next twenty minutes, I assume they’re preparing for surgery, but it happens more quickly than I expected. By the time they bring me in, they’ve already done the hard work, and all that is left is to pull the baby dramatically from the gaping wound. I make a stupid joke. My wife can’t laugh because she’s anaesthetised from the neck down. She looks scared.

Then, after under a minute of something happening behind a large screen. “Un petit garcon!”

I’m fully prepared to make a joke about my wife’s family finally having an heir and negating a state-enforced generation of shame2, but as she can’t laugh, and I don’t feel like explaining it to the medical staff, I decide against it.

My wife is taken into another room, and I can hold this weird little pre-human to my chest for half an hour or so, wondering what I’m supposed to be feeling—I’m mainly just worried about my wife. He’s then moved into a heated incubator and taken to the neonatology ward. There, he’s placed in a bed with oxygen, heating, and various monitors attached. The staff are reassuring, everything seems to be relatively stable.

The Beginning of Experience

Even when things are going well, it’s hard being a newborn. The helpless indignity of waking from a comfortable semi-conscious slumber and being brought into a sterile hospital filled with white light, weird sounds and cold air. The inability to express any noticeable emotion but distress, confusion and fear. This is what he looked like:

We move in with him after the first night. When he’s calm, he just looks adorably confused, as above. His heart rate and oxygen monitors are a constant reassurance. But when distressed, panic mode begins. His whimpers escalate into something more animal and frantic, we hear the beep and see the erratic signals, and the medical staff rush in, fit an oxygen mask and inject him with caffeine citrate. They tell us that the main risk is hypoxia (dangerously low oxygen levels). If this isn’t fixed, it can impede brain development or damage vital organs. In unstable infants, this can escalate rapidly, sometimes triggering cardiac or respiratory failure.

There’s something so visceral about the idea that your own distress, triggered by primordial fear or hunger, can cause brain damage, or even kill you.

Despite looking relatively calm when sleeping or being held, there’s never any sign of happiness or recognition. His life for the first week is a cycle of fragile stability made tragic by omnipresent tubes, and moments of genuinely life-threatening anguish.

This Is Everything

As with most people involved with EA and animal advocacy, I’m familiar with, and sympathetic to, the case for prioritising wild animal suffering.

I keep thinking of this while watching my son’s first days—watching him trying and failing to feed, unable to coordinate his tongue to swallow, relying on an obviously uncomfortable nasal tube because it’s the only way he can take in nutrition.

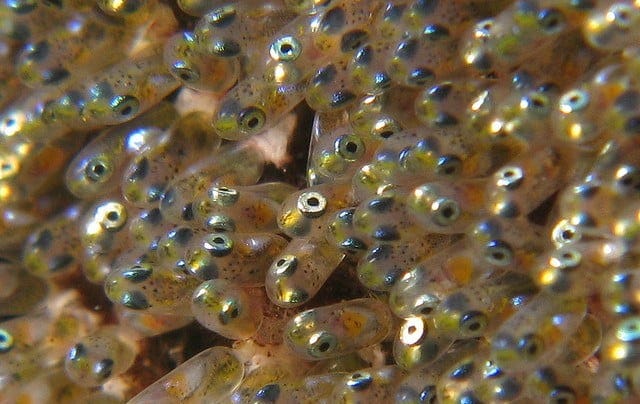

Most vertebrates3 are larval fish. 99%+ of wild fish larvae die within days. For these animals, being eaten by predators (about 75%, on average) is invariably the best outcome, because dying of starvation, temperature changes, or physiological failure (the other 25%) seems a lot worse.

When they do experiments starving baby fish to death (your reminder that ethics review boards have a very peculiar definition of ethics), they find that most sardines born in a single spawning don't even start exogenous feeding, and survive for a few days from existing energy reserves. This time is spent in a state of constant hunger stress, driven by an extremely high metabolism and increasing cortisol levels. For the vast majority who cannot secure food, their few hours-days of existence probably look a lot more like a desperate struggle until they gradually weaken and lose energy before dying.

They’re born too small. Like the premature human baby sat before me unable to suckle, most don't have the suction force to consume plankton.

Seeing my son in the ICU, hearing the babies in the adjacent rooms who have it worse, these numbers coalesce into something real. I realise that almost every animal currently, or ever, alive is a newborn. Underweight, fragile, and overwhelmed from the start. And for most of them, this is all there is. A flicker of life enters the world, flails around for oxygen or food, cries out for help if it can. And then vanishes.

There are an estimated 1020 fish born in that situation every year.

I’m not usually an emotional person, but there’s a moment where I’m watching this purple life-form gasping for air and realise: Fuck, this is effectively everything.

It’s the most intensely scope-sensitive emotion that I’d ever experienced.

Schrödinger’s baby

In the hospital, I’m constantly thinking about the question of whether my baby is actually experiencing anything at all. I can’t shake the sense that he exists in a kind of superposition—somewhere between consciousness and blank, silent unawareness.

I’ve never liked the cop-out of “proto-consciousness” or “an early, different form of consciousness.” Either there’s something it’s like to be a tiny baby, or there isn’t.

There’s evidence pointing in both directions. Intuitively, the younger the baby, the more their distress feels “algorithmic”. His cries are just mechanical outputs signalling hunger, discomfort, cold, or a need for contact. The shifts between crying and calm are sudden, as if disconnected from any inner continuity.

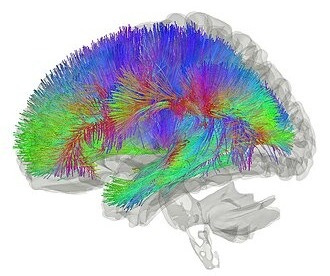

I try to recall what I’ve learned about different theories of consciousness. Babies don’t have the long-range thalamocortical connections necessary for integrating information across the brain, they don’t have the connectivity patterns associated with global workspace theory, such as broadcasting information across brain regions, and their default mode network, allowing them to self-reflect, doesn’t really activate until a few years in.

This might support the idea that consciousness hasn’t yet “switched on.” Even if pain pathways are firing and the baby is screaming his lungs out, that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s something it’s like for him to be in pain. Genuine suffering might only emerge after some kind of complex integration process, and that system may simply not be online yet.

In the first week, the baby’s behaviour is so alien, and his cognitive processes so simple, that it wouldn’t have surprised me to learn there was no conscious experience at all. I’d been effectively trying to bond with a sorting algorithm.

But then again, plenty of theories point the other way. Recurrent Processing Theory says that simple feedback loops in the brain might be enough for basic consciousness, and that this could appear around birth, or even before. Integrated Information Theory says consciousness arises wherever there’s enough “integrated complexity”, and sets the threshold surprisingly low. And then there’s weirder theories like panpsychism, which says consciousness is fundamental and built into matter itself, present in some form at every level.

In order to escape the “Schrödinger’s baby” dilemma, where infants are superposed between two extreme states: fully conscious or not at all, the usual solution is to find a middle ground. There’s a plausible-sounding argument that moral weight scales with complexity, and that suffering becomes more intense or meaningful as cognitive systems become more elaborate. Suffering and consciousness have a kind of mass: more neurons = more experience = more moral weight.

But this view feels both unjustified and suspiciously convenient. I can vaguely imagine a being experiencing a tiny, focused locus of extreme pain, just as I can imagine a vast, diffuse field of suffering. I’m genuinely not sure I know which is worse. And you can sense yourself and others wanting to feel this way. Believing that conscious experience and suffering scale neatly with complexity lets you justify leaving your child to “cry it out,” without feeling like you’re humiliating yourself by singing to a pot plant.

It would be easiest, albeit morally dodgy in other ways, to just “round down”, and assume that infants aren’t conscious and therefore can’t suffer. That would let us act more freely, ignore the distress, feel less manipulated, and save money on anaesthetic. But I’m not going to “do an Eliezer” and say, “my poorly thought-out model doesn’t assign moral weight to infants, so I’ll just ignore them.”

Instead, I’m left with a kind of bipolar moral uncertainty. Either my baby is suffering, and urgently needs my constant attention, or he’s a soft little automaton, an emotional shoggoth designed by evolution to extract resources through mimicry of pain and weaponised cuteness, with nothing truly going on inside.

On Feeling the Right Things

Premature babies can struggle for much longer. It’s months of agony and waiting for some parents, but we’re lucky. In the second week, he’s improving slowly. The tubes are gone, he’s starting to feed on his own. After a frustrating fortnight in the hospital, he becomes stable, and, by the third week, is finally allowed to leave.

In the hospital, the neonatology staff spoke to him in musical, lilting tones, calling him silly affectionate names like mon petit puce, mon petit chou, speaking to him as if he understands. You can see why this gentle compassion is probably optimal. Actually empathising with his distress would mean a plunge towards a baby’s level of bipolar psychosis. I still find it weird finding the words to speak to my adorable baby in a way that covers the possibility of existential horror and emptiness.

Caring about animals, you learn to live with that uncertainty: hoping consciousness is rare, while mostly acting as if it isn’t. Expected value calculations offer a kind of solace when you’re distributing limited resources across many beings with varying chances of consciousness. If newborn fishes are only 25% likely to be sentient and cows 85%, then you can make a rational trade-off or allocation of resources.

But that reasoning collapses when applied to a single, emotionally salient case like your own child. When the possibilities are stark, either he’s conscious or he isn’t, expected value becomes a kind of moral dodge. You can't act as if he's 50% there. Instead, you’re in a weird emotional limbo between both perspectives: sometimes suppressing empathy, telling yourself he’s just reflexes and noise, sometimes embracing him as fully sentient, trying to cultivate the love and compassion that might one day have a more certain object.

Into The Fifth Trimester

Things have been going well!

My son has grown into a more robust, rapidly-growing, and occasionally smiley little human. By the third month, he’s started smiling, and I can make him laugh. At five months, I’ve realised that, beyond the predictable baby chuckles at stupid faces and voices, he’s also learning to embody his delightfully toxic masculine side—breaking into seemingly genuine laughter at slightly violent slapstick hand-puppet theatre. His experience now seems to span a more recognisably human, and amusingly male, emotional range.

When he cries now, he really cries. There’s a beautiful Chinese phrase for it: 哭得撕心裂肺 (kū de sī xīn liè fèi)—to cry as if tearing apart one’s heart and splitting open one’s lungs.

His distress now feels more “real” and less algorithmic. It’s louder, sometimes more infrequent, and not always easily explained. Something feels particularly alive about that curious pre-sleep anguish, like a faint awareness that sleep brings an interruption of consistent selfhood—a mini death even—before a rebirth as a slightly updated human in the morning.

His behaviour is starting to feel less like that of a well-programmed NPC, and more erratic, expressive and unreasoning, as if a hyperactive child was let loose with the code. I find it impossible to see him as anything other than conscious.

The Most Beautiful Case For Net-Negativity

For anyone thinking of having a baby, let me assure you that they can bring so much joy into this world.

There’s a deep pleasure in his existence. An all-encompassing loveability that makes it impossible not to smile whenever in his company, even when he’s crying his little eyes out. He’s the first grandchild on all sides, a beacon of family continuity, bringing pride, joy and meaning to the grandparents. On the Chinese side, my in-laws’ doubts about my unconventional values and lifestyle have been quietly eroded by a healthy grandson and his conspicuous absence of an Asian epicanthic fold.

But the truth is, life hasn’t been kind to the little fellow so far. For the first five months of his existence, he’s been an adorable locus of suffering. If the intensity of a baby’s anguish is within an order-of-magnitude of an adult, then my son has likely endured more extreme negative experiences in the past two weeks than I have in the last two decades. He now has moments of obvious happiness, but also even more obvious, prolonged moments of distress. If I had to guess, I’d say his life is probably net-negative, but when he’s giggling with a mouthful of spittle, it’s laughably easy to pretend otherwise.

Of course I want him to be happy and free from suffering. But when we have to rely on subjective perceptions to determine whether we’ve achieved this, the desire for it to be true often causes us to deceive ourselves. But there are some moments, particularly looking back at that skinny, struggling, anguished thing in the weeks after birth, that I start to see the situation more clearly.

I’m not depressed or negative about this. Even in the worst case, I’m still an optimist. I believe that humanity can find a way to solve AI alignment, develop smarter and more ethical world systems, build the post-scarcity utopia we dream of, and strive for a universe free from suffering. In expectation, I think that my son’s life will be happier, more meaningful, and more beautiful than we could have dreamed of a generation ago.

But my main takeaway from having a child is probably a serious acceptance that, under most plausible theories of consciousness, the world is, and has always been, net-negative. And finally accepting everything that this implies, less based on this one life, more on what his first weeks reveal about the trillions of others lives born this year.

So here’s a hopeful message for prospective parents: your child will open your eyes to the true scale of suffering in the world, while looking so unbearably adorable that you’ll find yourself grinning inanely through the whole process.

Actually, she was speaking Chinese, so let’s translate literally: “my goat water has broken”; 羊水破了 (yángshuǐ pò le).

Her parents are actually quite enlightened - my mother-in-law is a dyed-in-the-wool communist, so absorbed the “women hold up half the sky” logic. My father-in-law is quite liberal and educated. However, upon seeing that my wife’s cousin was born female, the father (my wife’s step-uncle) famously welcomed his newborn daughter to the world with the phrase: 笨蛋 (bèndàn), you idiot (literally “stupid egg”).

Apologies for the vertebrate chauvinism here. Invertebrates need love too.