Who Should We Pay To Increase Birth Rates?

A blogpost not yet funded by the Government of Uzbekistan

When people in the pronatalist sphere talk about boosting birth rates, they’re usually thinking about their own high-income country—often the U.S. (One Billion Americans), or perhaps the countries at the forefront of the global fertility crisis, such as Japan or South Korea.

People in this sphere might have particular personal, eugenic, or geopolitical aims here, therefore have a strong reason to promote fertility in their chosen country or region. This may all be good and noble, but if you’re concerned about the global trend of fertility decline, as many people are, you have to approach this issue in a very different way.

One common approach, as discussed by Robin Hanson and Zvi, is simply paying people to have kids. Lots of countries try to soften the blow of childbirth on peoples’ finances with parental leave, free childcare and small (occasionally large) tax breaks. And it works! These studies find that even a small cash bonus increases the birth rate, but, because of the substantial costs, foregone income, and potential career setbacks, these policies never go anywhere close to actually make having kids seem affordable, let alone a sensible financial decision.

I agree with their claims that, if “money for kids” doesn’t seem to be working, we’re probably not paying them enough.

But it could also be that we’re not paying the right people!

For people concerned about the long term stagnation caused by fertility decline, is it optimal paying people in rich countries to keep the birth rate from plummetting? The obvious problem is that paying someone in a rich country to do (relatively) unskilled labour—childbirth and child-rearing—is a glaringly inefficient use of both money and labour. You need a very strong bias towards this rich country to want to do this!

So assuming no strong bias towards a given country, let’s just ask the question—if you want to incentivise childbirth in any country in the world to maximise the outcomes you want, which country would you choose?

Perhaps a poorer country?

Paying people to have kids clearly works, if you pay them enough. But people in different countries value money differently. People tend to value money roughly in proportion to their per capita GDP; it’s almost a tautology to say that people are, on average, willing to substitute a year’s worth of labour for their countries’ average annual salary.

Imagine a global policy where, for 24 year olds, if you have a kid before you’re 30 we’ll give you 2x your countries’ per capita GDP for each child. This would work incredibly well! Someone in Luxembourg would revel at the idea of getting $250k for having an extra child, but someone in Burundi might be equally thrilled to get $1600 for each child!

If you found a way of only targeting people who would not have an additional child absent this incentive, this might look like subsidising 100,000 extra births in Burundi for $160 million—an amazing deal if your main concern is just averting a global demographic collapse!

But optimising for pure numbers doesn’t seem like the best strategy. As much as you might think that pro-natalist cultures are a good thing, the current fertility level in Burundi allows very little parental and material investment per child. According to conventional development economics, we’d prefer a reduction in fertility in very poor countries, to allow for more investment by parents and a better ratio of working people to dependents (see the Demographic Dividend). Also, sadly, a child in Burundi is far less likely to contribute great things to the world than someone in a richer country—they’re also less likely to have an enjoyable life, and more likely to die young.

But there’s probably a good middle ground between Luxembourg and Burundi. So this means that we have a trade-off on our hands. How can we maximise value for money?

The best bang for your buck (probably a pun in there)

My thinking here is that you want people to have as good a life as possible for as low a price as possible. So let’s draw up a mini-model to calculate this. I see four main variables to suggest whether it’s a good country to nudge towards higher birth rates:

Wealth: All else equal, the cheaper the better. Let’s just use GDP per capita as a simple metric.

Education Level: We want people to be smart and make sensible life choices. Let’s just stick in years of effective schooling.

Subjective quality of life: There’s always a bit of bias in these kinds of questions, but I think they do capture something about how nice it is to live in a country; let’s go for life satisfaction.

Likelihood of having more offspring: You want your investment to pay off in more children down the line. Getting a Hong-Konger to have kids is probably an evolutionary dead-end, while getting a Togolese to have kids might get you 5 or 6 extra kids within 30 years. Let’s stick in Total Fertility Rate.

So we’re looking for a country that’s poor and with an already high birth rate, but disproportionately educated and happy.

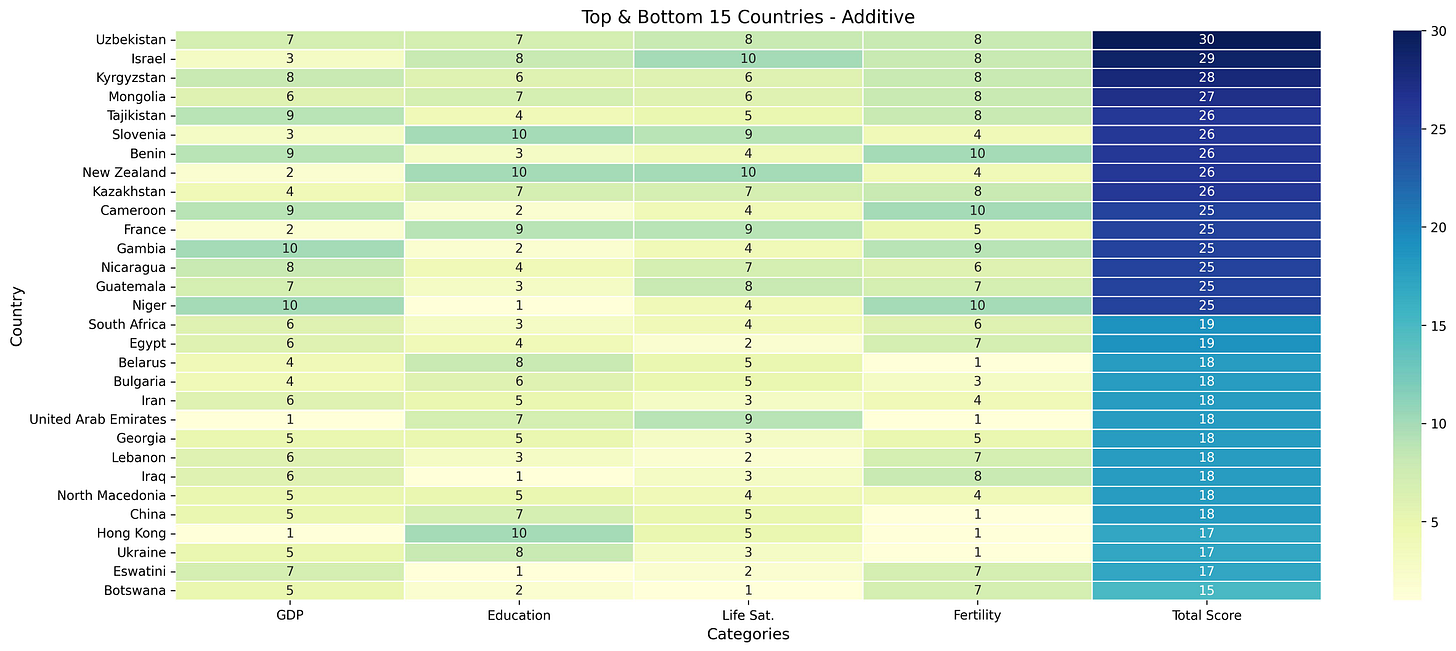

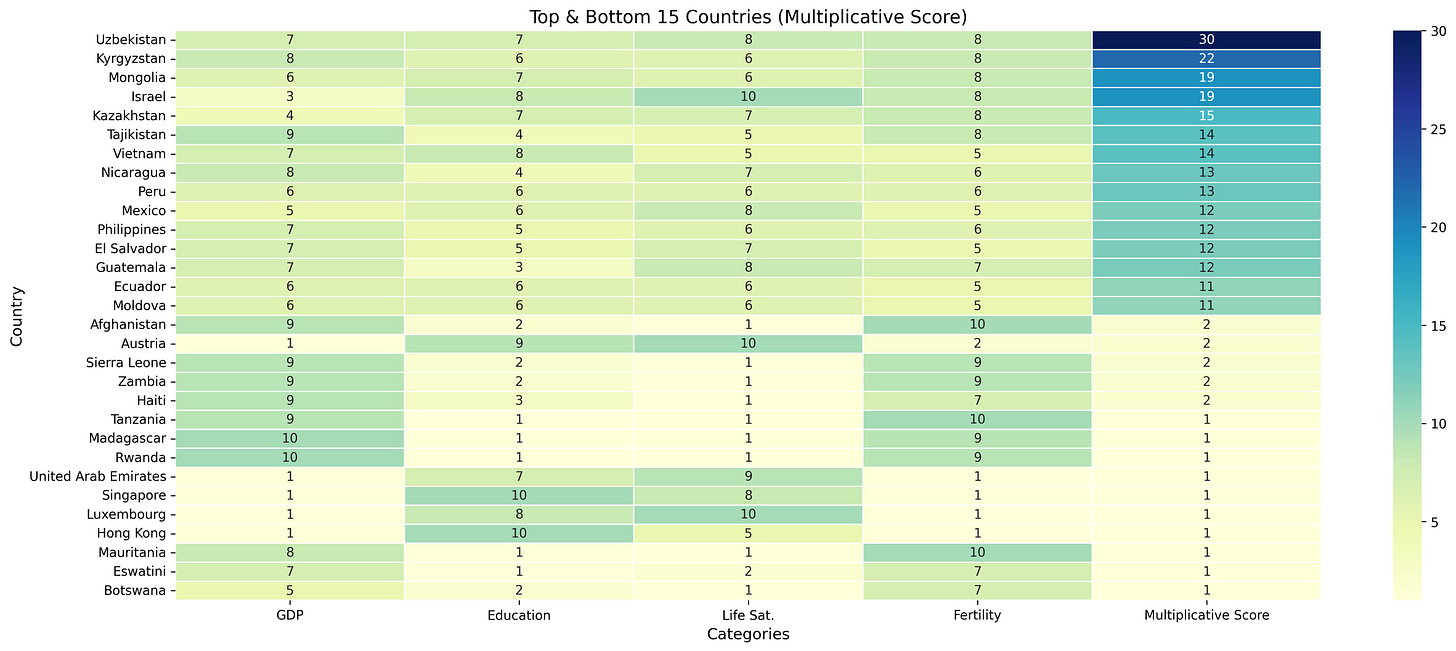

I put this into a toy model here. To radically simplify, I put all the countries into deciles according to these variables, scored them from 1-10, then added together.

The results are in! Based on these factors, we should be paying people in Central Asia and Israel to have more kids!

With the additive model (adding together the four categories), Slovenia, New Zealand and Benin also make it into the top 10. If we turn the model multiplicative, rewarding moderate scores on all categories, South America and Southeast Asia start looking better, because they score moderately well on all metrics, but Central Asia always looks impressive.

But according to both models, with only $3,010 GDP per capita (nominal), and a relatively happy, educated and fertile populace, your best choice for increasing human fertility is paying Uzbek women to have more children!

Who should we not be paying to have kids? Poor old Botswana and Eswatini look bad for their relatively high GDP, but low reported quality of life (adding sky-high HIV rates would also be a warning sign these countries). China, Hong Kong and Ukraine suffer from low fertility, and not being particularly happy. Middle-East and North African countries also don’t look great.

You might have some kind of racial, ethnoreligious or cultural hierarchy theory about how you want the world to look, which is all fine if that’s your cup of tea. I personally like the idea of boosting underpopulated countries like Mongolia, but you might also want to think about future population trends, ideological alignment or producing top 0.1% talent. But overall, I think this model works pretty well.

What might this look like in practice?

Now that we’ve proven beyond doubt who we want to pay for having children, the next challenge is tackling the how. How can we throw our dollars at fecund Central Asian women in a way that actually increases birth rates, rather than simply rewarding births that would have happened anyway?

It will surely be incredibly easy to find someone who will be willing to say that they’re having a child, and getting them to accept your money. The difficulty would be ensuring that your money actually produces kids compared to the counterfactual.

I can think of a few ways of doing this:

The Auction Model

Couples interested in having a baby could set up profiles on a platform, describing their situation and financial constraints. Donors (or philanthropists) could then bid on which couples they want to support. Instead of a single upfront payment, support could be distributed gradually—perhaps spread across the first five years of the child's life—making sure families get ongoing assistance, births are verified, and potential fraud is kept in check.

This has the advantage of being market based and efficient. It targets the “marginal parent”, who would decide to have a kid with only a "financial nudge”. The downside; the risk of fraud, or worse (e.g. forcing women to have children) would make this a bit scary to implement.

The Universal Basic Income (UBI) Model

A philanthropist or government could give a nominal payment to every new parent in a target country. Let’s say Mongolia. This would function like a baby bonus, automatically applied across the board.

You could get in touch with the government of Mongolia, tell them that every family in Mongolia can receive payments for each new child, and let them take care of the logistics.

This has the advantage of being very simple and scalable, with no risk of selection bias. The big inefficiency is the same as that of UBI: it risks a very low counterfactual impact. Many parents would receive money for births that would have happened anyway.

The Targeted NGO Model

A specialised nonprofit organization, such as a pronatalist family planning clinic, could work on the ground to identify financial barriers to parenthood. The NGO would find cases where financial constraints actually delay or prevent births, then find a payment structure that works.

The big advantage here would be that you could use the NGO staff to identify families who were looking to have kids for the right reasons, and are constrained just by finances. The problems are mainly the standard problems with NGO work—there might be a lack of transparency, corruption, mission creep, and general inefficiency.

Do I think this is a good idea?

I’m not a hardcore pronatalist—I believe in the meat-eater problem and there are clearly some negative impacts from overpopulation on issues like biodiversity and land-use. But I also spend a bit of time worrying about aging populations, demographic collapse, and the risk of stagnation over the next few decades.

How do I feel about the countries that come out of the model? Uzbekistan is one of the least free countries in the world, and there are concerns associated with terrorism and radical Islam. But not all of Central Asia has these issues—I visited Kyrgyzstan (2nd or 3rd in the model) last summer, and it’s a lovely country. Despite some creeping authoritarian concerns, people seem mostly happy, and nudging Kyrgyz birth rates up by one child per woman seems like it might be a nice thing for the world.

And it could be very cheap.

I won’t get into the exact economics here, but it’s possible that even tiny bonuses can work. An additional bonus of $1000 (about 2% of GDP) was enough to get Australian parents to increase their fertility!

If families in Central Asian countries would be willing to have extra children for a similarly small nudge—say a month’s average wage, the cost could be as low as a few hundred dollars per child!

This is far lower than the cost of saving a child’s life from disease in similar regions, so I think it’s possible that this could be an ethical, even an effectively altruistic thing to do. Animal welfare impacts, the main negative of high birth rates, would also hit less hard in these regions. Central Asians consume considerably less of the animals that suffer more from factory farming—aquatic animals and chickens—and Central Asian fat-bottomed sheep seem very happy.

In the longer term (boldly assuming no AI-driven catastrophe or leap towards utopia) transferring money from rich countries to more child-friendly countries to boost fertility could be one of the only levers we have for stabilising the human population.

I initially started writing this as a thought experiment, but I’m starting to genuinely think it might be worth getting the mechanisms in place to potentially achieve this.

And if any of my (currently) 4 subscribers happens to be a Central Asian president, don't hesitate to reach out!

This proposal is genius in its simplicity. Unfortunately, simple proposals also tend to get overlooked.